OUR HISTORY - DARTMOOR, DEVON AND WORLD WAR TWO

In an effort to preserve precious heritage, in the form of the memories and first-hand experiences of the local wartime generation, MED Theatre’s ‘Dartmoor, Devon and World War Two’ project offered the opportunity for younger members of the rural Devon communities to carry out research and oral history interviews that can be used in the creation of various creative outputs. On this page you will find some of the highlights of the interviews carried out with very special members of our community.

May Ashford

May was born in 1923 and although her house in Plymouth was damaged, her family remained in the South West throughout the war, spending some time in Notter Bridge in a converted railway carriage. May also worked as a GPO telephonist during the war, receiving the warning calls for air raids. Here are some of May’s memories:

“Our Anderson shelters were at the bottom of the garden and so were the others, so all the shelters were in a little group. And they used to say, as long as you can hear the bombs it means you’re okay, because they say you don’t hear when it’s…

Well the shelter just at the back of us received a direct hit and I didn’t hear that bomb, but you can feel it, you can feel the air being compressed.”

–

Memories of VE Day:

–

“I was eighteen and there was a consignment of bananas and I was too old to get one. Mind you I did get one because what we had as a family we shared and I did have a banana, but I wasn’t supposed to”

–

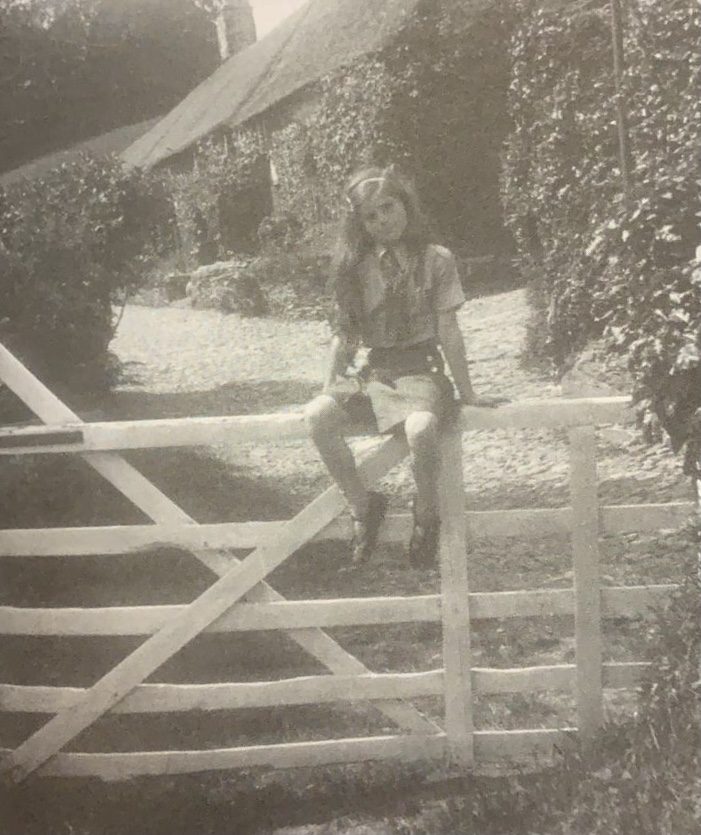

Working as a volunteer Land Girl:

–

“…We used to receive the air raid message yellow, and that was to say stand by. Air raid warning purple, that was to say it was imminent, and air raid warning red. And when it was air red warning red, we had several numbers we had to phone to tell them, to spread the word. We had to sit with the thing open, you know we weren’t shut off at all we had to keep the thing open so that we responded right away. When it was air raid warning you weren’t supposed to talk at that time, but we did of course. And one of the operators said, oh air raid warning red, why don’t we have a change and said air raid warning magenta? She was told off like mad about that, oh yes.”

Kenneth Wheeler

Ken was born in July 1928 and remained in the Plymouth area throughout the war. He worked in a bakery and his favourite way to pass his free time was to go to the cinema and escape the world outside.

“We could hear the bombs coming, we could hear them whistling and coming towards us, and Father said, down, and I threw myself on the floor; on the concrete. And I laid there looking at this candle, directly in front of me and the first bomb dropped to just below us and I watched the candle go out and I watched the dust rise off the ground, about three inches, and then drop back down.

Then the second bomb landed at the top of our street and the same thing happened again, the candle went out and lit itself and the dust shoved up three inches and fell back down. And that happened four bombs in a row; as they exploded this occurrence happened and I was mesmerised to see this dust rise and go back down and to see this candle go out and light itself again. I was absolutely stunned.

To me it was wonderful and I wasn’t afraid, I just thought it was so educational you know it was wonderful; it was something I hadn’t seen.”

–

Memories of people escaping the Blitz by heading to Dartmoor:

“There was all sorts of people; rich, poor, they just went up in their hundreds onto the moors. Some of them had tents, some of them had just tarpaulins or something like that and they just made a rough shelter to get under.”

–

“And then on the 6th June it was my birthday. My mother always put a sixpence in my shoe on my birthday, now sixpence might not seem much to you but to me it was a fortune. And I was 14 and I left school on the Friday and I started work on the Monday. No that’s when I started work… I was 16 when D-Day started, it was my 16th, 16 years old, and I went out to put my shoes on and looking for sixpence, a tanner it was called, and I was looking for my tanner and I said, Mum there’s no sixpence here. And she said no I’ve got a better birthday present for you, and I said what’s that? She said, our troops have landed in Normandy. And then she said, that’s the best present you’ll have this day and it was.”

Making comparisons to the COVID-19 Pandemic:

Euan Bowater

When Euan was only six or seven he started attending a school on Exmoor that taught young Jewish children who had been brought to England in the Kindertransport rescue effort in the months leading up to WW2. Here, Euan shares his memories of the school with us.

Kindertransport

Kindertransport (Children’s Transport) was the informal name of a series of rescue efforts which brought thousands of refugee Jewish children to Great Britain from Nazi Germany between 1938 and 1940.

British authorities agreed to allow an unspecified number of children under the age of 17 to enter Great Britain from Germany and German-annexed territories (Austria and the Czech lands). [c.Holocaust Encyclopedia]

“The school was a bigish gabled house beside the river Exe, close to the road bridge in Exford. Had good-sized lawn, mini-forest of tall Leylandis to one side and on its far side was bounded by a low wall beyond which a grass field sloped gently to the river.

I went to it aged 6 or maybe just 7.Before going, I was taken to see it – on School Concert day. A line of pupils stretched across the school’s large main room from a piano played by Naomi Bernberg, the headmistress, and sang things like, and in particular, “Hearts of oak are our ships, hearts of oak have our men, there’ll always be an England, steady boys steady (or was it ‘ready’?)”. The biggest and loudest singer and nearest to the piano was – I later learned – Naomi’s eldest son, Benedict. He at once became my hero, and it made me long to sing and play songs.

The year was, almost certainly, 1942: mid War.The school had about, I guess, 20 to 25 pupils. All were Jewish (as of course was Naomi) except Jane, me and David Hudson whose parents had, like ours, thought this a better bet than the ‘village school’. David Hudson told me he and I were “gentiles”, implying a difference. I’d never heard that word before. Nor, for that matter, had I ever heard of Jews before, but don’t remember spending any mental time researching the matter. How those children – and Naomi who was clearly a mother-figure as well as headmistress – came to be there, and where from, I wasn’t curious and never knew. The guess of anyone with War history knowledge is as good as mine. All, except we gentiles who lived at home, lived in the house.The school day began with Naomi playing the piano while all pupils walked round the big table in the middle of the main room a few times with books balanced on our heads. It was, I gathered in due course, considered good for “deportment”. From time to time at the end of that ceremony (why then? but memory tells me it was) we were issued with ‘pocket money’ – three pennies, I think – and then immediately invited to give some of it to help “plant a tree in Palestine” (I knew where that was because I liked maps) by buying a stamp to stick in a book.In that main room Naomi did lots of reading to us, including from a Walter Scott book in which Guy Manwaring was the hero, and The Cloister and the Hearth by Charles Reade, and the story of the willow pattern on plates; also extracts from The Iliad, and a marionette theatre and puppet figures were created from cardboard for a performance of the part of the Iliad where Achilles and Hector fight and Hector is (very distressingly) killed and dragged.We were taught how to grow broad beans on blotting paper in ex-jam jars, and from budded twigs we collected were taught and named different tree species. We rehearsed and performed a play about Joseph – from him and his coat of many colours being chucked in a pit by his brothers to his triumphs in Egypt. (I was a non-speaking brother). As a result it is one of the only Old Testament stories I know. We also did a Chinese-story play, and went by van (horsebox probably) in the dark to perform it in the village hall of nearby Winsford as well as in school. I had a line in that one: “Aren’t you ever going to chop off my head?” impatiently!The only other teacher I remember (were there others? I’ve no idea) we were told to call ‘Madame’. She was big, blowsy, blonde, and sought to teach French (and may have been). I didn’t like her or French. But she or someone now forgotten did manage to teach me to read and write, strictly phonetically and by doing joined up aaaaaas or bbbbbb etc etc multiple times across pages; a bit of basic maths too. All that happened in the other school room, which had desks instead of big table. But no great proportion of school time was, in my memory, spent in class.Piano lessons were available, a teacher from outside coming in; and I was looking forward to having some but gave up disillusioned when it wasn’t tunes like “Hearts of Oak”.There were no – that I can remember – any children’s books or anything else intended specifically for children anywhere about.In breaks, ‘He’ was played on the lawn and amid the (unpleasantly smelly) Leylandi trees. ‘He’ ran about and everyone else tried to catch/touch him or her, and whoever did first became ‘He’ instead. Jane was a speedy and frequent He.Some afternoons we would walk down to the river and dig clay from its banks and bring it back to roll into sausages to make pots; or go with sacks to the fields where foxgloves grew to gather their leaves “for the wounded soldiers” (digitalis)

Ron ZAPLE

Ron was born in 1934 and was evacuated for a short period to Stoke Climsland but was otherwise in the Plymouth area.

“The war really, we weren’t afraid of the war because we didn’t… Oh yes you knew some bombs dropped, and you lost some of your school friends but it didn’t affect you like that, not as a child. We just went out playing and then you picked up some shrapnel and who had the biggest piece of shrapnel, oh that was something worth looking for in the gutters. In those days, you played out in the street. Played ball, football, skipping, no problem at all. You didn’t worry about cars because there was no cars about; very few anyway.”

–

About food rationing:

–

“…near St. Budeaux they had an encampment up there of American soldiers. And we used to go up there and say, any gum chum? I can remember saying it to them, got any gum chum? And they would toss you out a packet of chewing gum. Until the dockyard copper came around and chased you all away.”

–

“The biggest part of it was poor mother was on her own and I can realise now she had five children to look after. It was a bit of a problem for the poor girl and father was… Of course the Repulse was sunk and luckily father was a survivor and I can’t remember the next ship he went on but that one was sunk as well.”

MEMORIES FROM OUR 1940s TEA party audience

On the 3rd of July 2021, MED Theatre hosted a 1940’s themed tea party at The Sentry in Moretonhampstead. During the course of the afternoon, visitors were invited to share memories of their war experience. Below are a few examples of these memories.

“My Dad was a Rear Gunner and did many sorties and thankfully survived.”

Shopping: “Mum didn’t queue for her shopping like other mums. For some reason she had it delivered in a van during the war- better than click and collect!

Memories of my Grandad’s: “He lived in London as a young boy during the war. On one trip to school with the other mothers and their children, they had to dive over a low garden wall as the street [that] they were on began to get gunned by an overhead aircraft.”

“I was evacuated to Moretonhampstead 1939 as a 5 year old. I have been in Moreton for 82 years. Today it brought back many memories”- Bill Field

“My great-grandmother left home at 16 [and] lied about her age [in order] to join the airforce. Her name was JOAN.”

VE Day: “Dad decided we all needed ice-cream. He cycled 3 miles to the next village and back. When he arrived with our newspaper-covered ice-cream the rest of the street joined the street party and he had to ride off again for more ice-cream! That’s devotion!